Star Wars vs. Star Trek...vs. Doctor Who

Where Doctor Who Fits in the Star Wars vs. Star Trek Debate (Using Science Fiction Magazine Terminology)

Every science fiction viewer grapples with the unwanted question at least once: Star Wars or Star Trek?

I never understood the Star Wars vs. Star Trek debate. It’s seen as an age-old stand off, but it’s not quite fair to compare two shows just because they’re long-lasting, popular, set in space, and have far too many sequels. After all, they’re not even the same genre, so what basis could you compare them by? The previously-mentioned similarities are a poor foundation for critique.

Star Trek is generally seen as a science fiction. Perhaps not as hard of a science fiction as some would like, but it uses space to herald an expansive future by exploring the what-ifs of its day and age. Its setting is an extension of Earth, and the inventions have some semblance of logical explanation - in fact, multiple real-life technological innovations were designed by viewers who were inspired by Star Trek tech.

Conversely, Star Wars is set “a long time ago” (you know the rest) and holds space as a backdrop for an expansive system comprised of its own non-Earth-ian customs. It’s an imagined world, the same as Tolkien’s imagined Middle-earth, and similar to the Lord of the Rings, Star Wars’ conflict reflects universal themes instead of issues that might be related to a specific decade. But while Tolkien expands his world by detailing the intricacies of the ages - through time - Star Wars expands its world through space. Star Wars is not quite a science fiction, despite its trappings. And yet, despite sharing more similarity with the purposes of fantasy, it is embraced by fans of both genres.

Comparing one of the two shows against Doctor Who would be a more interesting debate than leaving the two to themselves. Doctor Who is old - at least as long-lasting as Star Trek and Star Wars. It’s endured parallel dimensions and multiple revivals. It thrives in space. It hasn’t had as many complaints over its sequels compared to the American staples, but its continual revivals and reboots have forced an entirely different issue of needing to carefully distinguish between a ‘series’ and a ‘season’ (not to mention the new headache caused by the most recent series being referred to as both series and season, with differing numbers). And, like Star Wars, Doctor Who’s genre is tricky to pin down.

When the Doctor Who 60th Anniversary specials released during November 2023, outlets declared that the show had shifted away from science fiction and towards fantasy. The sentiment originated from newly-returning showrunner Russel T. Davies’s comment during an interview with Radio Times Magazine:

“The show is taking a sly step towards fantasy, which will annoy people to whom it’s a hard science-fiction show…Episode two next year is wildly fantasy. Completely making up scenarios on-screen that we’ve never been able to show before. But the following episode is proper hard science-fiction.”

The problem with Davies’s comment is that it conflates individual episodes with the whole of the series. Doctor Who has never fully been a hard science fiction (a term which I will better define in a moment). It has all the trappings of science, but at its heart, it’s an adventure through time and space, and science has nothing to do with it - even if Earth is one of the Doctor’s most frequent destinations.

As a result of the thriving American pulp magazine scene in the early 1900s, ideas about what science fiction and fantasy were or should be began to distinguish themselves. Of course, the discussion continued well into the 1980s and never concretely settled, so the categories remain somewhat permeable. In terms of literary variety and imagination, that’s probably a good thing - after all, an entire movement within the 1950s sf community launched because some authors thought that the necessary components for ‘hard science fiction’ made the genre too restrictive, and science fiction today is fairly wide-reaching. The downside to these floppier terms is that it’s difficult to define all the stories that don’t quite fit into either.

So what is hard science fiction? What makes one show more science fiction than another? Since these terms and categories were largely formed by American pulp magazines and have never really left, here’s a brief overview of the decades when the modern science fiction genre really kicked off. Hopefully, it’ll give context for how sf became ‘hard science fiction’ and ‘all the other science fiction, I guess:’

When dime novels (cheap youth-oriented adventure literature) died down in the late 1800s, pulp magazines (cheap adult-oriented fiction literature) became the US’s reigning literary entertainment until World War II. Science fiction was common, though a lot of it was sensationalized. Two editors tried extremely hard to elevate science fiction’s reputation.

Hugo Gernsback launched Amazing Stories in 1926, the first magazine to offer just science fiction. He requested stories that included scientific accuracy; most of his stories centered around futuristic inventions and technology. The Hugo awards are named after him.

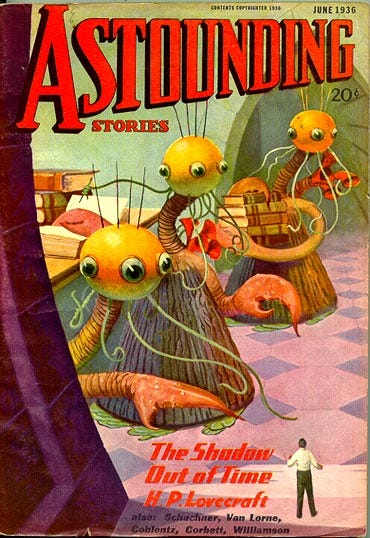

Stanly G. Weinbaum was not an editor, but his 1934 short story A Martian Odyssey influenced the shift into modern science fiction by changing how aliens were written. Before, aliens were either humans in a different flavor or two-dimensional characters. Weinbaum fleshed aliens out by treating them as a unique group with non-Earth-ian customs and views.

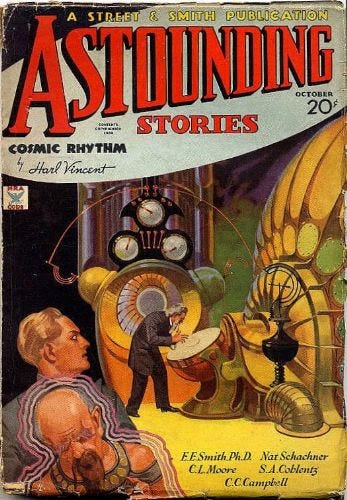

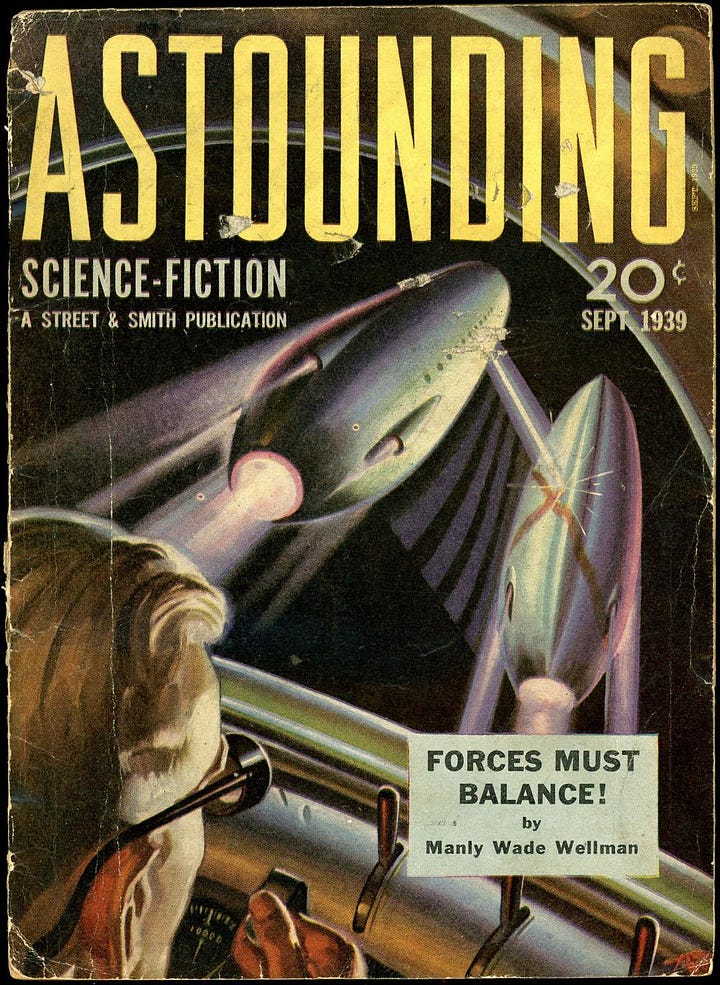

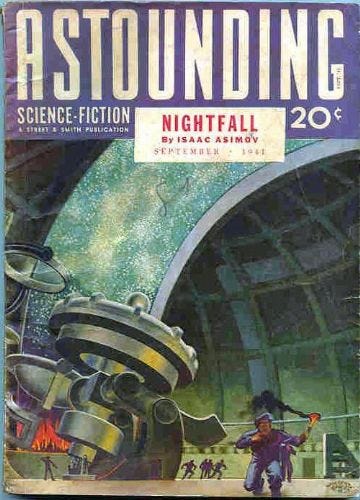

John Campbell took over as editor for Astounding Stories (today known as Analog Science Fiction and Fact) in the late 1930s. His term at Astounding began the Golden Age of Science Fiction. He insisted on scientific accuracy and fleshed-out characters. He asked writers to make stories “as though they were going to be printed as contemporary fiction in a magazine of the 22nd century.” He shifted the focus from the inventions to the situations caused by people who had to deal with the inventions. Although the tone in these stories varied (and the dangers of such scientific explorations weren’t shied away from), Campbell generally wanted authors to write with a supportive view of science.

Of course, call yourself the Golden Age of Science Fiction and certain ideas are going to stick well after the age has moved on. The term ‘hard science fiction’ didn’t get used (in print, anyways) until 1957, but by that time, the genre had settled on “better scientific accuracy = better science fiction,” which meant sf writers who disagreed felt the need to change the criteria again. Enter New Wave science fiction of the 1960s and 70s, especially “soft” science fiction, and Ursula K. Le Guin, and now there are two main categories sf falls into.

To the best that I can gather, here is how the main gradients of science fiction break down:

Hard Science Fiction: sf stories that are based around an exploration of science and/or don’t contradict known science. The science is key to the plot. The Martian by Andy Weir would be a modern example of this.

Soft Science Fiction: sf stories that focus more on characters than scientific concepts or scientific accuracy and/or that focus on less-quantifiable sciences (ex. sociology or political science).

Science Fiction: the catch-all term for most fiction science-related speculations or explorations.

And just so fantasy doesn’t get left out:

Weird fiction: a catch-all term for fantasy, horror, Lovecraftian monsters, and other non-science-fiction speculative works. This term was used less after the 1930s.

Fantasy: Scenarios that are scientifically implausible but logically believable based on the information provided in the story.

Star Trek, which references more than it explains its science and technology, and which focuses more on the character dynamics than the scientific discoveries they make, isn’t a hard science fiction. But it’s still based on the principles of known science; it’s followed the Campbellian fashion of presenting an advanced future in an everyday way. It has also adapted plots from science fiction magazine stories, which helps ground the genre.

In terms of science, Star Wars also references rather than explains its technology, but it additionally has its own version of science - the Force - which can’t be explained through our scientific principles. The Force is well-established in the Star Wars universe, with its own rules and expectations. Scientifically, Star Wars is a fantasy.

But Doctor Who shares aspects of both, thematically and scientifically. It contains Star Trek’s need to reflect and relate to the state of the modern times, no matter which times the Doctor ends up exploring. It shares Star Wars’ extended and somewhat malleable lore. It acts off of known physics and science, and yet, with the same confidence, includes unknown and unverifiable alien technology, barely explained, likely not referenced again once an episode ends.

At one point, magazine writers did try to make terms for the science-related stories that didn’t fit science fiction. Many of them didn’t last, and most of the ones that held on are considered subdivisions of soft science fiction instead of their own genre, but to add two of these categories into the mix:

s p a c e o p e r a

Science Fantasy ???

A space opera is an adventure set in space. People have reused and rebooted the term with different meanings, but at the end of the day, it’s all about the high-stakes galactic fighting and the expansive environment and the character drama. Star Wars can add space opera to its arsenal.1

Science fantasy is a term that sounds like it could solve all of the genre differentiation problems. The only issue is that science fantasy itself has never been well defined. It ranges from “fantasy that uses a science aesthetic” to “story that cohesively blends both genres.” Some pre-Gernsback pulp science fiction might now be considered science fantasy. To get introduced to the genre, imagine someone gluing gears onto a keyboard and getting away with calling it steampunk. Then add more and more steam-powered devices based on what the writer decides to show.

I would categorize Doctor Who as a science fantasy. When the show needs a quick explanation for a device that saves the day, the Doctor might shoot scientific gibberish at a mile a minute, or he might rely on established gravitational law. Some episodes center around technology and a society’s reaction to it, some episodes use technology as the backdrop for exploring crew dynamics, and some episodes introduce fantastic creatures or scenarios with only a slap-on “they’re really aliens” explanation to get by. The show indicates that humans only know a fraction of the depths of science, but it doesn’t feel the need to explain the rest; it just needs to maintain the logical order of the Doctor Who world - much like a fantasy. Within that world, its science draws upon Earth’s own principles, but it often extends beyond it. The show’s writers have long felt comfortable applying Arthur C. Clarke’s concept that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” To the people who live in Doctor Who’s London, Doctor Who is science fiction. To the people who live in London’s London, Doctor Who is fantasy. But it’s still a science fiction.

If Doctor Who is a science fantasy, it takes its plots from pre-Gernsback and its lessons from post-Campbell. It offers swashbuckling adventures and visits to unique alien cultures, and it relies on science just as much as it needs to in order to get the job done.

After all, it is a show about time travel. It would be within expectations for it to pick genre criteria from any decade it chooses.

I began this post with the intention of proposing that Star Wars vs. Doctor Who was a better comparison than Star Wars vs. Star Trek, believing they shared more in common. At this point, I don’t think there is a comparison, genre-wise. They’re all space-related shows that lean in different directions. Viewer’s preference and overlapping fanbase are the biggest uniting criteria, and fans can argue from that standpoint endlessly.2

I considered other possible contenders to add to the list, but there aren’t many shows that can rival Star Wars, Star Trek, or Doctor Who in terms of fanbase and legacy. I think Firefly could have competed, if it had lasted longer.

Then again, Firefly already has its own comparisons against Cowboy Bebop, so maybe it doesn’t need an extra contender. Let the space cowboys nurse their early endings, and let the other three live long and prosper. They can even retain their labels as science fictions if it makes for better diplomacy.

After all, none of them hold a candle to The Twilight Zone, and The Twilight Zone covers every genre under the speculative sun.

Agree? Disagree? Sporadic thoughts? Please, let me know your comments.

Thanks for reading.

Also, shout-out to Clifford Stumme. My initial draft of this was fairly short. After I read his article, “The True Difference between Sci-Fi and Fantasy that No One Talks About,” I expanded this post because I liked the way he included his sources and analysis and wanted to include more of the sources I was drawing from as well.

Honestly, with enough reasoning, Star Wars can fall into any category the viewer pleases to fit it in. It does align very closely with space opera, though.

If you’re wondering about my order, it’s Doctor Who > Star Wars > Star Trek, but I’ve also watched Star Trek the least out of the three. That may change with time.

I feel like the ability to drift freely between various poles of the genre spectrum is a strength of Doctor Who, and a big part of why it's endured all these years.