Thunderbolts* and the necessity of leaving room for lore

Never underestimate the appeal of a group of heroes living in the same house.

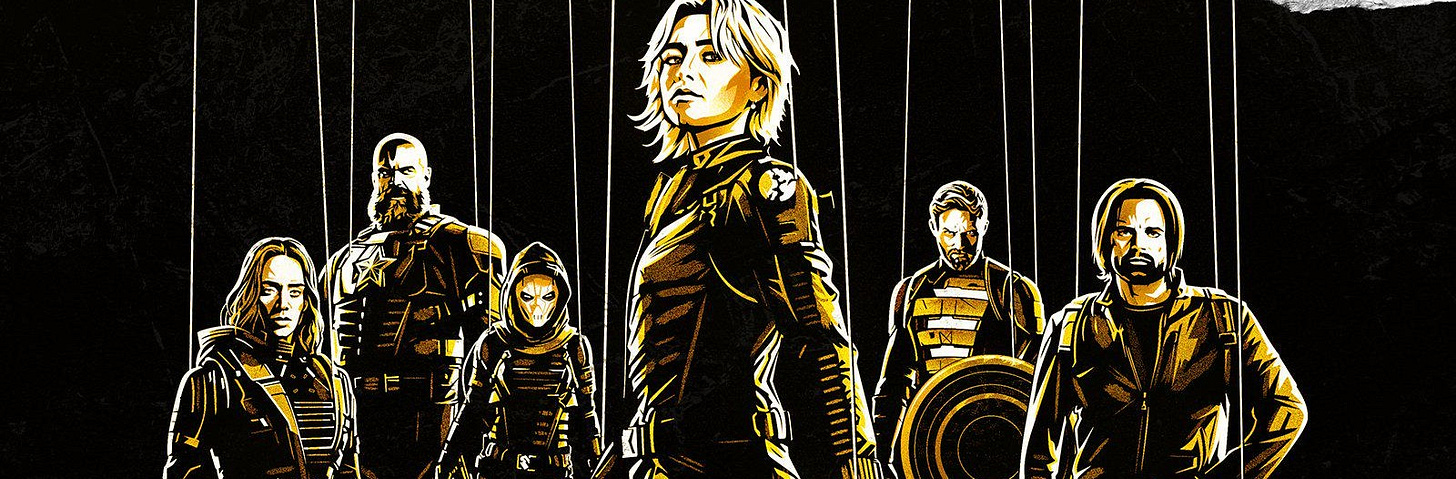

After years of not letting characters get in the way of plot in the MCU, Thunderbolts* was THE character interaction movie. It gave the characters so much priority that it even offered the fandom a boon by placing a whole fourteen months between the last scene and the end credits.

Fourteen months of speculation. Fourteen months of the Thunderbolts living in the Avengers Tower.

A very detailed and persuasive essay could be written1 about how important the Avengers Tower is to the health of the MCU fandom. It offers so much room for the characters to breathe.

The earlier phases in the MCU had this concept down to a science. Each movie offered:

interactions between characters,

interactions between characters outside of the confines of the mission, and

a large assumed timeframe of unseen interaction.

In other words, the earlier movies let the fans run wild in their speculations about what heroes were up to during their downtime. The movies were the blueprint for each character’s personality. The fans did the rest.

Why is the Avengers Tower in particular so important?

The Tower is where the Avengers met up, but it was also where Tony Stark lived, and given that at least three members of the original Avengers didn’t have confirmed housing at the time, some people just assumed that the other Avengers decided to live at the Tower, too. Cue analysis, headcanons, fanart, fanfictions, you name it. The creative side of the fandom was at its peak in those middle phase days. It’s a good thing the fanbase was so enthusiastic and active at that point, too, because some of those middle phase movies…2

However, unlike Phase 4’s mediocre response, the fan disappointment associated with Phase 2 films only boosted the desire to reimagine and expand on (or ignore) what was given.

Aside from the general excitement of knowing that all of this was building to something, a reason why Phase 2 was forgiven and Phase 4 was rejected was that Phase 4 didn’t let its characters breathe.

Instead of investing the time in forming new character models, Marvel brought back characters who had already gone through the work of connecting to the audience. The audience had their expectations set up. The MCU found a way to make sequels without going through the need for a first film.

But there’s no staying power there. Spider-Man: No Way Home wasn’t a movie so much as an event. There’s nothing wrong with that. Movies are meant to entertain, and it was a truly special experience. But I couldn’t imagine watching No Way Home at home. It wasn’t a movie; it was an event.

The problem is that Marvel treated new characters the same as the nostalgia-bait characters. It shoehorned them into the plot and fast-tracked them into being loved on-screen as if they were simply nostalgic characters the audience failed to remember, which is a surefire way to make the audience hate new characters. You can’t assume people will or should like your characters. You have to give them the time for the audience to trust them. You have to offer their personality and character and let the audience make their own judgements. You have to let them breathe.

Take Riri Williams from Black Panther: Wakanda Forever as an example. She could have been interesting if she was given enough time to be fully introduced, but she’s just thrown into the mix of the movie with the assumption that fans of Tony Stark will like anyone who bears a resemblance to him.

Her introduction as a late Stark protégé begs comparison to Tony introducing Peter Parker. Before recruiting him, Tony sat Peter down to assure himself that Peter had the right mindset about being a hero. Almost the opposite happens in Wakanda Forever, where conflict is caused because Riri makes inventions without thinking about the consequences. The concept is similar to how Tony acted at the beginning of Iron Man, but this connection isn’t emphasized. Tony took responsibility and matured—that was the whole arc of the film. Riri doubled down on her irresponsibility, shifted blame, and glowed up to main sidekick in the third act anyway. It was grossly unearned.

Ironheart has recently released,3 so the expanded time from the tv format could do her good. I just have no interest in watching.

Of Phase 4’s forced attempts of introducing a character in a movie, however, there is one successful exception.

Shang-Chi gave a solid depiction of Shaun’s life outside of superheroism and offered enough time to wade through his plot-relevant backstory. The only problem? Shang-Chi the character is completely absent from all the other movies, and he’s also geographically separated by the rest of the United States. California’s lack of relevance in the MCU (sorry California) and film development delays have kept him from affecting other storylines. Please, Marvel. Bring him in. It’s been 4 years.

Then again, maybe his absence was for the best. This way, Shaun can just directly enter the upcoming Avengers movies, which people are somewhat excited for, and fans don’t have to scour a half-dozen mediocre films for a collective five minutes of Shang-Chi teases.

Most Marvel projects in the past phase (Shang-Chi included) have tried to overstuff themselves. Abandoned plot threads are messily knotted by new characters who replace introduction with indulgence and lack of planning. Thunderbolts* brought Marvel back to classic form. Its plot was surprisingly simple, but it was competent and straightforward, and it kept its focus on the characters. That’s all it needed to do. I am happy to imagine the rest.

Apparently, so were the mostly-dormant creative side of the Avengers fanbase.

Fandoms are a mixed bag. Fans can get up in arms over the littlest things. Fanart can be well-produced or plagiaristic or stolen or reused. Fanfiction can be well-produced and compelling or something you wouldn’t nudge with a 10,000 feet pole. But when it works, it works, and it worked overtime for Marvel back in 2013.

When Captain America: Civil War split up the Avengers in 2016, it also fractured the Fandom. There were no more Avengers to imagine over. There was no Tower to center them all around. There was only a looking back to the happy days of when they all (allegedly) existed at their Midtown Manhattan haunt. The activity ebbed and flowed, but it definitely dwindled as the years passed. It was more than halved post-Endgame.

But when Thunderbolts* released, a flicker of that same passion and concentrated fan activity returned—and a good amount of it was shamelessly centered around the confirmation that these new heroes were staying at the Tower.

The uptick in activity is not as big as those middle phase days, and the ratio of quality to “don’t go near” content is not as golden as it used to be, and the angles are less analytical. The activity has also already mellowed, but this might just be the limbo of post-theater/pre-digital release. Next month will show if the excitement lasts. Still, even the short-term enthusiasm is a win for Marvel. The nature of the interest plays off of the nostalgia of the Avengers at the Tower, but Thunderbolts* still made people willing to engage in Marvel’s present.

After observing various fan interpretations of characters unfold over the past two months, I’ve realized how little was actually explained about 1) character dynamics and 2) Bob’s powers. There were no solo films for these characters. Previous backstory comes from prequels and sequels, and a good amount of those stories were mid. If you’re going off of just Thunderbolts*, which I am assuming a chunk of these people are, then yeah, the sky is the limit, up to a point. Instead of asking fans to put energy into over-explained, underdeveloped plots, Thunderbolts* clears the air with a straightforward premise and offers fans the opportunity to do their own guesswork, to speculate and explore, with the promise that the characters will build on where they left off fourteen months prior.

Because most of these characters are actively being compared to better-known Avengers, I would expect some stereotypes to run into similar veins. However, with the exception of Alexei occasionally being Thor 2.0, the creative side of the fanbase has kept these characters flandarized to their own history. Strangely enough, Bob, who lacks a clear counterpart or previous film tie-in, is more susceptible to this treatment. I’ve noticed Bob getting treated like Peter Parker 2.0. I’m guessing this is because Bob looks like Tom Holland and Tom’s Peter Parker has been infantilized to oblivion since basically his debut. The physical resemblance in some of the scenes is uncanny, but Peter Parker is a teenager and Bob is a former meth addict who’s pushing thirty. Not a lot of information has been given about Bob, but there’s definitely enough to clarify that difference.

Thinking back to Civil War, the MCU has potentially put its momentum into a bind by setting up an immediate Civil War between the Thunderbolts and whoever Sam Wilson picks for his Avengers. If Sam’s is the official team moving forward, I don’t anticipate the Thunderbolts getting much screen time in future movies. I hope they won’t be killed off or turned into jokes, which would fly against the point of this movie’s message. But we’ll see how it goes.

For fourteen months, they’ve got the Tower. We’ll deal with the fallout afterwards.

I won’t write it, but it could be written.

I’m starting to think that Marvel’s just not the best with even-numbered phases.

conveniently showing how long I’ve procrastinated on this post.

OK I hear you, but Taskmaster tho.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com